Michelin heritage

Over 130 years of adventures

Driven by materials science and technological progress for more than 130 years, Michelin has been at the origin of the greatest advances in the field of mobility and beyond. Let yourself be transported to the heart of the fabulous History of a Group that continues to innovate to transform your daily life.

Genesis

1829

The beginnings of rubber

in Clermont-Ferrand

A Scottish woman named Elisabeth Pugh-Barker married Édouard Daubrée, an entrepreneur from Auvergne. She was the niece of the chemist Charles Macintosh, who had discovered that rubber was soluble in benzine.

Remembering the bouncing balls her uncle made for her, she began to make them herself in her husband’s workshop.

Her initiative brought rubber to Clermont-Ferrand, making a lasting impression!

1832

The Barbier-Daubrée company

1889

The creation of Michelin & Cie

The first major innovations

1891

The first modern tire

Using this tire, Charles Terront won the Paris-Brest-Paris race more than eight hours ahead of the second competitor!

1895

Riding on air

This feat allowed the Michelin brothers to showcase the benefits of tires to the world, particularly their reliability, resistance, safety, and comfort.

1898

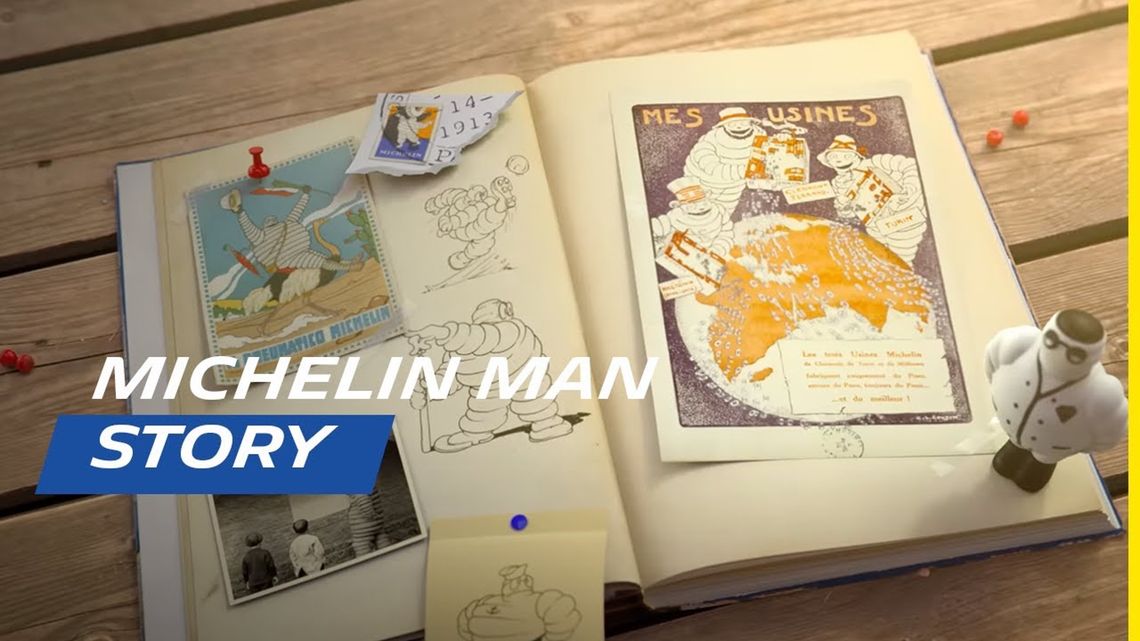

The gentleman of tires

1899

The need for speed

1900

The first MICHELIN Guide

The builders

1906

All over the world

1914

“Our future is in the air!”

1929

The Michelines’ story

1931

Road signs

1935

Michelin, Citroën, and the 2CV

1937

The marriage of rubber and steel

The Radial area

1946

The invention of the Radial tire

1955

François Michelin, the Radial ambassador

1965

The importance of research

1973

A champion in all categories

1975

Toward new horizons

1981

First acquisitions

A new drive

1991

From father to son

1992

The birth of the 'Green Tire*'

*Name relating to the concept of 'lower environmental impact tire'

1998

Yes to sustainable mobility

2000

The Michelin Man, Best Logo of the Century

2005

The succession

Jean-Dominique Senard, who had been a Managing Partner since 2007, took over from Rollier in 2012 and served as Chairman of the Michelin Group until May 2019.

2016

Vers de nouveaux territoires de croissance

Today, this booking platform has been renamed TheFork, and is present in more than 20 European countries.

The use of mergers and acquisitions allows the company to create more value and establish itself in new sectors of activity, around and beyond tires.

All-sustainable approach

2017

Imagining the future

2018

The year of celebrations

2018 also marked Michelin’s 400th victory in MotoGP™, thanks to more than 40 years of innovative technologies at the highest level of motorcycle racing.

2019

Riding without air

2020

Tomorrow, everything will be sustainable

2021

'MICHELIN IN MOTION', the strategy for 2030

In 2021, through its new strategic plan 'Michelin in Motion', the Group reaffirms its conviction that sustainable growth can only be envisaged by taking into account planetary limits and by exercising authentic social and societal responsibility.

Michelin is committed to continuing its targeted growth in tires and investing in new territories in connected mobility solutions and high-tech materials.

2022

“MICHELIN IN MOTION”, great progress

Michelin provides new evidence of its ability to implement its 'Michelin in Motion' strategy. The Group relies on its unique innovative strength, its in-depth knowledge of its customers, their uses and their needs, as well as its distinctive know-how inherited from its mastery of materials and data.

For Michelin, learning together, so that everyone finds their place and progresses within the Company, constitutes a major performance lever. With this conviction in mind, the Group implements the necessary conditions for the development of its employees throughout their professional careers.

2023

Development beyond mobility

The Group intends to position itself as a key player in polymer composite solutions. The Group's growth is achieved both through the growth of its existing activities, as well as through external growth operations, such as the acquisition of the Flex Composite Group in 2023, which made it possible to increase the turnover of the High Technology Materials division by 20%.

Its distinctive know-how allows it to conquer high-growth markets that value innovation and performance, and to offer ever more differentiating offers, products and services.